If you’ve been following our series on the history of printing presses, it’s been quite a ride. We started in China way back in the 800s A.D. We checked in with Gutenberg and the information explosion he ignited throughout Renaissance Europe. And in our last piece, we looked at the Industrial Revolution, where techniques that still exist today – such as lithography and the rotary press – were born.

(If you haven’t read these first entries yet, go ahead. We’ll wait.)

While these earlier advances laid the ground for today’s print technology, there was still room for improvement. Several technological advancements since the Industrial Revolution have improved printing quality and efficiency by orders of magnitude over what was possible just a century ago.

Print is not dead. Indeed, it’s thriving in the modern world. The latest printing innovations are melding the digital and physical realms.

Here are three of the highlights of the last century-plus of printing history:

1890: Flexography Is Invented

Up to this point, we’ve mostly covered techniques and technology for printing on flat paper surfaces, like books and signs. But what about uneven surfaces like product packaging? Enter flexography.

Flexography, as the name suggests, involves wrapping a flexible printing plate around a rotary cylinder. As the cylinder spins, it imprints ink onto the printing surface.

The first flexographic press was introduced in England by Bibby, Baron and Sons. It was derided as “Bibby’s Folly” because the water-based ink smeared easily. But more robust inks were eventually developed, and over the years, the flexographic process has been refined.

Flexography is now considered one of the most efficient and cost-effective methods of commercial printing. Rubber plates have been replaced by light-sensitive polymers, and more recently, computer-guided laser etching.

Because flexography impresses ink directly onto the printing surface in one step and uses quick-drying ink, it has become the go-to choice for product packaging.

1906: CMYK makes its debut.

In the 19th century, Thomas Young and Herman von Helmholtz theorized that vision is based on a trichromatic principle – that is, there are three types of photoreceptors in the eye, each sensitive to a specific range of light. Thus, any hue detectable by the human eye would depend on a mix of those three ranges.

This scientific background formed the basis for four letters any printing professional would recognize: CMYK.

As it turns out, the Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow tones closely match the colors detected by those three types of photoreceptors, allowing printing presses to duplicate the colors we see with the naked eye. Add in Black (or “Key”) to create very dark, deep colors, and you have a wide range of tones.

The first company to incorporate this four-color process into printing was the Eagle Printing Ink Company in 1906. CMYK printing works by applying separate layers of the Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black inks. Instead of being applied as large swaths of color, however, the tones are applied as tiny dots.

So, if you wanted to print this circle:

…a CMYK color process printer would evenly distribute dots within the circle, with 55% of the dots being Cyan ink, 24% being Magenta ink, 68% being Yellow ink, and 36% being Black ink.

This color process is still used today, with Orange, Green and Violet occasionally joining the mix to add even more color possibilities.

1993: Digital Printing Eliminates the Plates

You may not have heard of Benny Landa, but his invention was just as revolutionary as Gutenberg’s.

In 1971, while conducting research on liquid toners, Landa developed a cutting-edge new way to print: charged pigmented particles in a liquid carrier. He founded Indigo Digital Printing in 1977, and in 1993, he released the E-Print 1000, the world’s first digital color printing press.

Instead of using plates (and the setup time they required), Landa’s exciting new process allowed a computer file to be transmitted directly to the printer, which would then be reproduced using these pigments.

Digital presses allowed a wide range of new and exciting print options. For example, the presses could convey variable data, allowing for each printed item in a run to look different (think of labels with sequential serial numbers, for example).

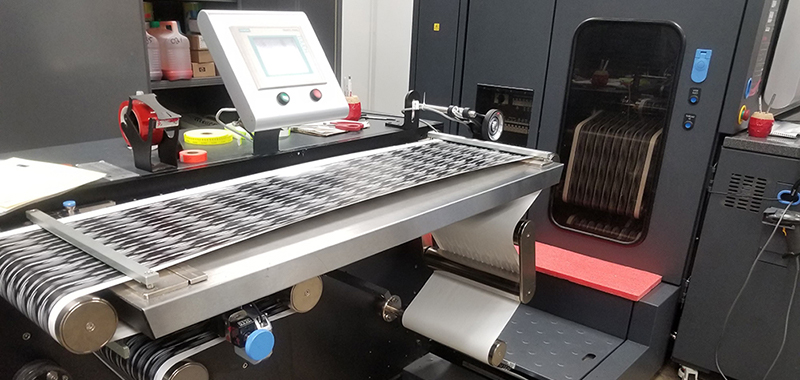

Since the advent of the digital press, digital printing technology has been taken in new and exciting directions. Now, hybrid presses offer the flexibility of digital with the stunning visual effects and customization of flexographic printing, even for short print runs.

What Will the Future Bring?

We hope you’ve enjoyed our four-part series on the history of printing. And we hope you’ve learned something. There won’t be a part five – not for a while, anyway. But you can be sure the coming years will bring plenty of exciting new developments in the art of printing. Subscribe to our blog and be among the first to discover what comes next.